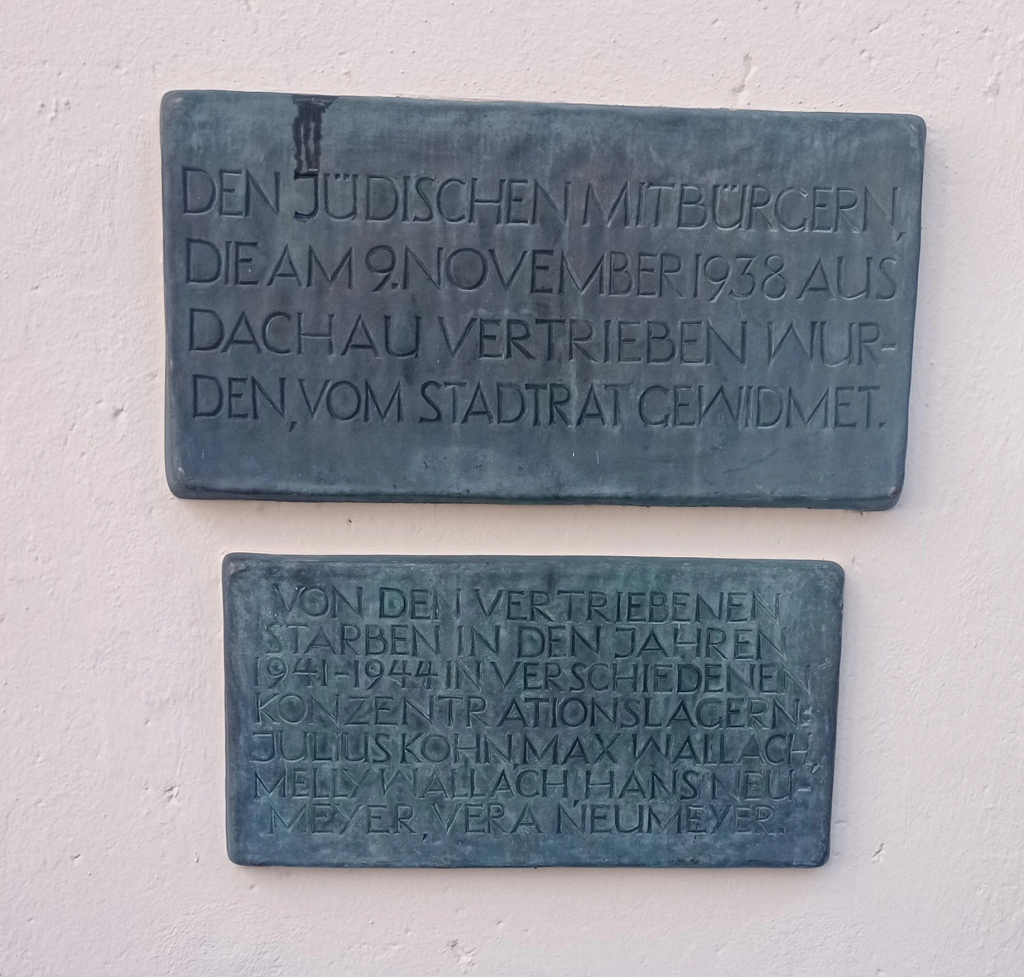

November 8 1938: fifteen Jews evicted by the Nazis from their home town, Dachau. November 8 2023: seven descendants from those people are in Dachau again at the invitation of the town. They are from three former Dachau families: Jamie Hall from the Wallachs, Alex and Mark Tittel from the Jaffés, and Tobias Newland, Stephen and Nic Locke plus myself, Tim Locke, from the Neumeyers.

It is the first time we have all met each other. Our Dachau antecedents lived a few hundred metres from each other: a five-minute stroll along Hermann Stockmannstrasse passes the Stolpersteine (memorial brass plaques) to each of those families. Parts of our families made it out of Nazi Germany to the United Kingdom, which is why we ourselves exist. We’re now geographically dispersed: Jamie in Athens, Alex and Mark in Texas, Nic in New York and Stephen, Tobias and myself in England.

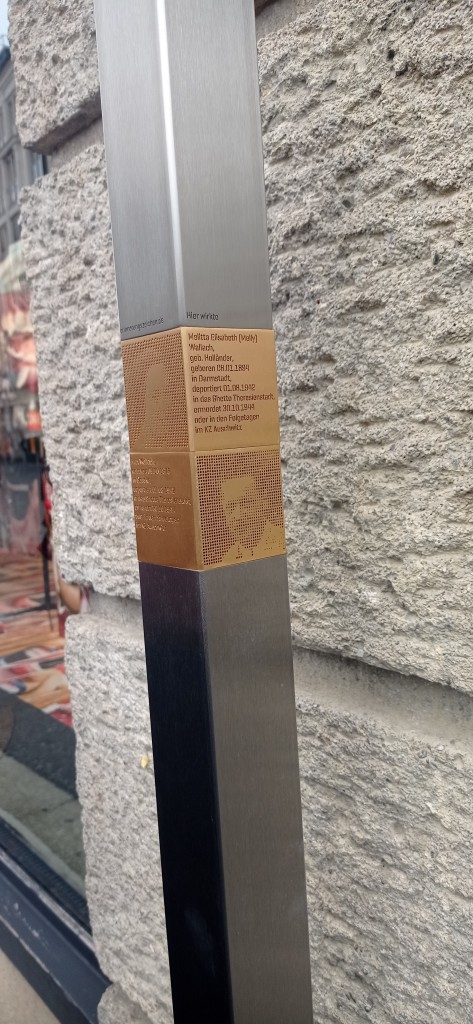

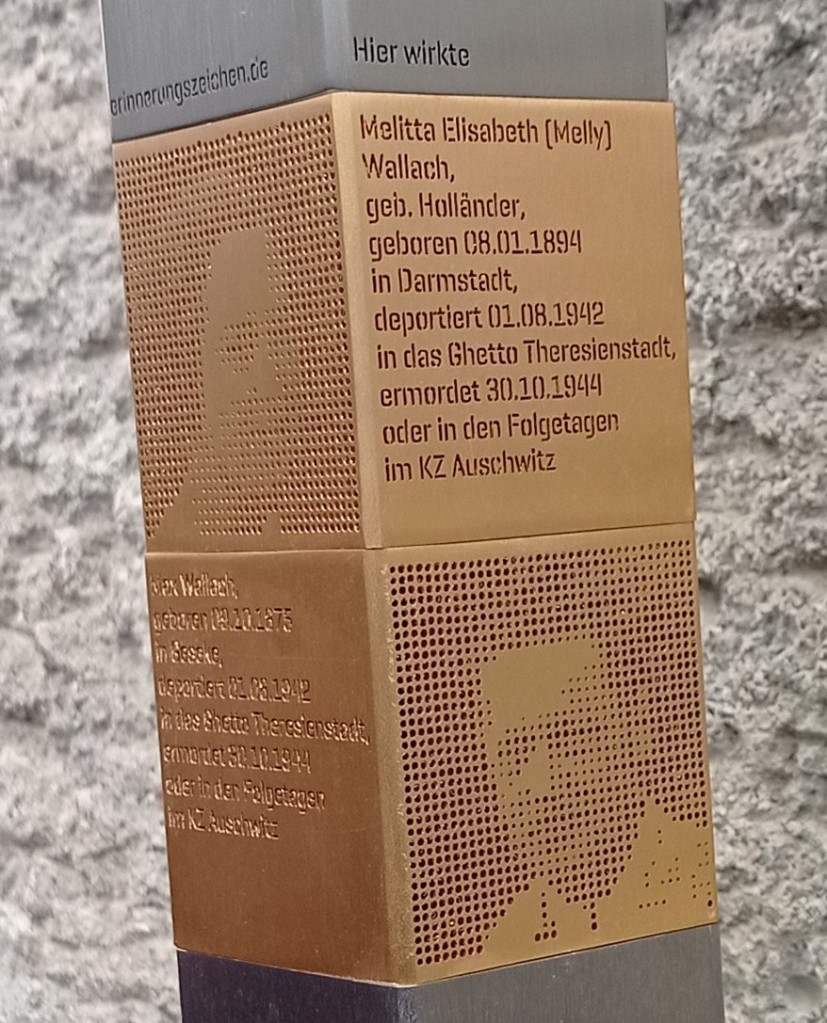

Jamie’s antecedents owned a textile factory in Dachau that supplied the celebrated Wallach store in Munich, selling colourful textiles, dirndls and the like. That came to a catastrophic end under the Nazis, with the family forced to sell the business and Max and his wife Melitta perished in Auschwitz. The Wallach store kept going, and was returned to Wallach ownership until its sale to the Loden-Frey department store in 1983, who kept the Wallach name until the store’s closure in 2004. Jamie has tracked down a huge store of Wallach fabrics in a Bavarian village, and has established the Wallach Project “to preserve, re-tell, and re-imagine the artistic and cultural heritage of the Wallach brother’s company.” Click here to read more. (I have previously posted about the Wallachs on this blog here.)

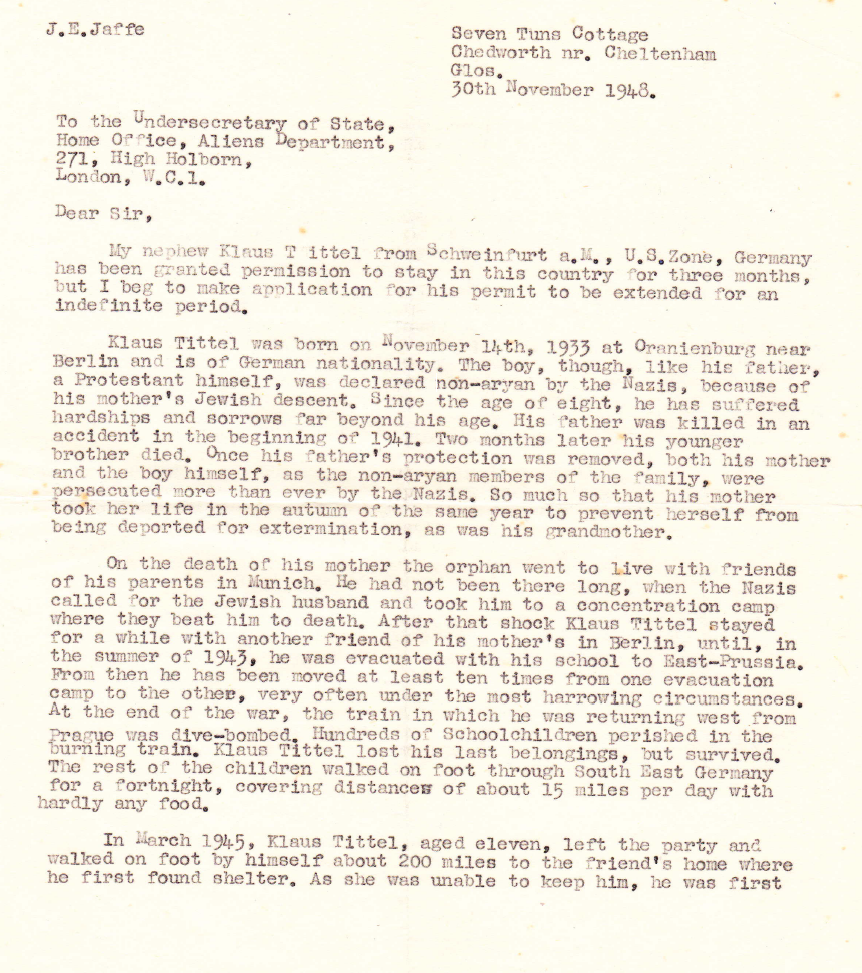

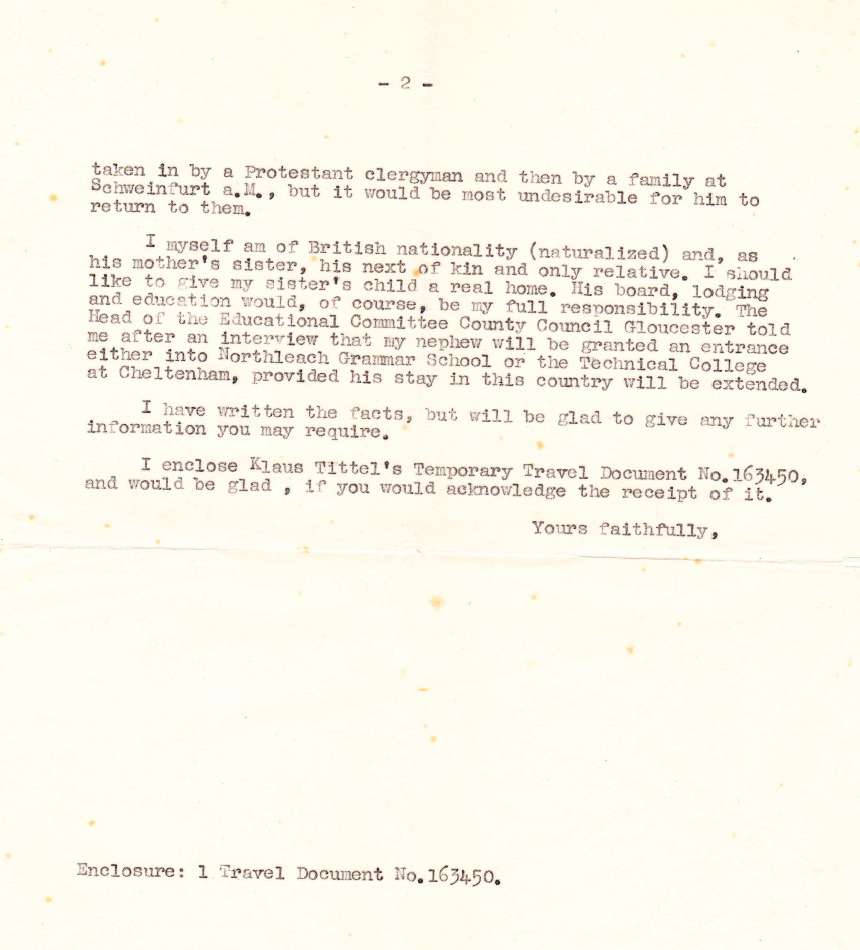

Alex and his brother Mark Tittel are the great grandchildren of Alice Jaffé and grand nephews of Johanna Jaffé, both of whom were residents of Dachau during the 1930s. Their father Frank Tittel (originally named Klaus) who was born in Germany in 1933 is a survivor from those darkest of times. His father, Dr. Heinrich Tittel, who was not Jewish, was killed in an avalanche in Austria during a ski trip in January 1941. Less than 3 months later, Klaus’ two-year-old brother Rolf contracted an ear infection and died after the local hospital in Schweinfurt refused to treat his illness because the mother of Rolf and Klaus, Hilde Tittel (née Jaffé) was Jewish.

Later that same year, Klaus made the grisly discovery of his mother’s lifeless body in the kitchen next to the gas stove Hilde used to end her life after facing an increasing amount of Nazi persecution, including the threat of deportation. His aunt Johanna Jaffé (‘Tante Hanni’) had managed to escape to England in 1939; however, her mother Alice Jaffé was murdered in a Auschwitz in 1944. Tante Hanni successfully pleaded with the British authorities in 1948 to allow Klaus, the orphaned son of her sister, permission to live wither her in England.

Subsequently and to his aunt’s great pride and joy, Klaus was able to get a scholarship to attend Oxford University where he earned a PhD in physics and would later became a pioneer in laser research and a distinguished professor of Electrical Engineering at Rice University in Houston, Texas.

Face to face with the town

The seven of us spend the morning of our final day giving hour-long presentations/workshops – different ones for each of the Tittels, Jaffés and Neumeyers – to classes of schoolchildren: ours were all 15 years of age – the same age as our mother Ruth when she came to England with her brother Raymond on a Kindertransport, leaving their parents behind on the platform of Munich Hauptbahnhof at midnight on 9 May 1939. We deliver the presentation in German. A large proportion of our attentive audience are refugee children. One is from a family that had to flee from the war in Bosnia, another from Albania, whose family escaped to Greece where they were forced to take up the Greek Orthodox religion.

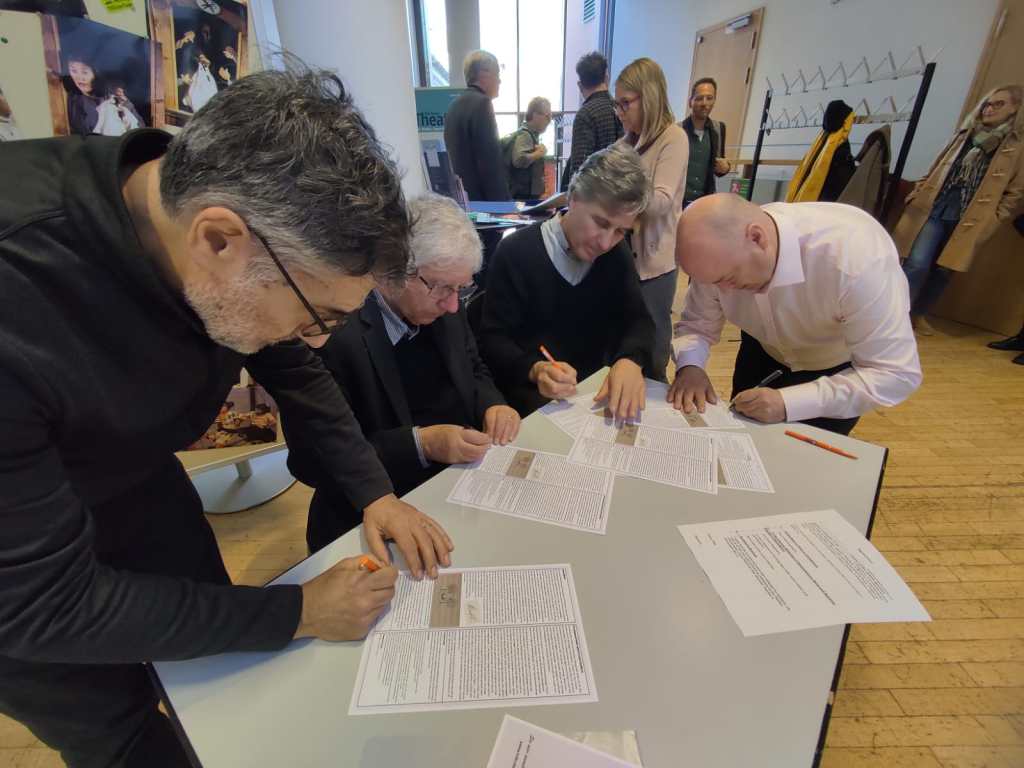

That evening we’re in the Ludwig-Thoma Haus conference centre in Dachau, with the local MP, mayor, press and over a hundred members of the public. Pupils from the Josef Effner High School read the audience to the stories of the three families. Those children who escaped to Britain along with Ruth and Raymond Neumeyer were Jamie’s grandfather Franz Wallach (who later changed his name to Frank Wallace) and Johanna Jaffé, the great aunt of Alex and Mark, whose father Frank himself is still alive but was too frail to travel to this event.

I can only fully agree with Abba Naor when he says that a Palestinian mother mourns for her child just as much as does an Israeli mother. And yet against the backdrop of the mass murder of European Jews carried out by Germany, it is also our duty to clearly state from whom the terror against Israel, from whom the massacres of completely innocent women, men and children were carried out with bestial brutality on 7 October 2023. Hamas alone bears responsibility for this and for the current war, just as Germany bore responsibility for the Second World War and the Shoah, and thus ultimately also for the civilian victims of the Allied war against Hitler’s Germany. My appeal to all of you here and also to the pupils present is that we must always keep these connections in mind. It began in 1938 with pogroms and ended in 1945 with the mass extermination of 6 million people. This must never be allowed to happen again.

Extract of the speech given by Florian Hartmann, Mayor of Dachau, introducing the seven of us to the stage

The seven of us go on stage, along with the chairman, Jürgen Müller Hohagen. We know Jürgen well: he met Ruth and Nic back in 2005 when Stolpersteine were being installed outside the Neumeyer house, which coincidentally is immediately next door to the pretty villa he lives in with his wife Ingeborg. He is a psychotherapist, and since moving to Dachau some years ago has a specialism in the effects of the Holocaust on the human psyche. His questions stimulate lengthy answers from us all – we speak in English and he paraphrases into German, though most of the audience seem to get what we say.

He asks us to single out family members who perished in the Holocaust. I slightly circumvent the question by recollecting both my grandparents. I never met them, of course, but they had a vast presence in our house in Sydenham, where I was born and grew up. The photo of Vera was in a frame by my mother’s bed, her beautiful face among two other pictures – a postcard of Dachau and the outside of the Neumeyer house. Upstairs in the often chilly, uninhabited sewing room at the top of our strangely rambling house was the pen and ink portrait of a benign-looking man in dark glasses, whom I learnt was Hans; his blindness terrified me from an early age.

In a moving panel discussion, the descendants of three former Dachau families, Jaffé, Wallach and Neumeyer, spoke about their persecuted parents, grandparents and great-grandparents and also about how they themselves live with the legacy of these difficult memories.

The conversation was moderated with a lot of empathy by the Dachau psychotherapist Jürgen Müller-Hohagen, who that evening saw himself “first and foremost as a neighbor”: He and his wife Ingeborg live next to the Neumeyers’ former home. Both have been in contact with the descendants of those expelled from Dachau for years and looked after the guests during the three days of their visit to Dachau.

This personal, friendly relationship and Müller-Hohagen’s expertise in the effects of persecution-related trauma that last generations created an atmosphere in which the descendants could also talk about painful memories. It was a very special evening that made it clear that the work of remembrance has lost none of its necessity and relevance.

Sabine Gerhardus of the Dachauer Forum, who posted this on the Forum’s blog.

When Jürgen asks us how we learned what had happened to our families, we all have the same sort of response: it was gradual, we only learnt fitfully, no one ever sat down and told us the whole story at once, and survivors wanted to put the past behind them and not talk about it. Nic mentions whispered conversations in German. In my case I was always aware of a German connection – our house was full of German books and other objects, there were German relatives and we had German-style Christmases. But I didn’t get the picture at all until I was about nine, when playing some war game with various boys – England against the Germans – and one of them said ‘I hate Germans’. My friend Peter, whose parents had obviously found out more by talking with my own parents, said ‘don’t say that, as Tim’s mother is German and she had to escape from the Nazis on a train to England’.

Thereafter things slotted into place very gradually, but was made much easier when Hans Holzhaider, a journalist from the Sud Deutsche Zeitung, came to England in the mid 1980s and interviewed Ruth and Raymond while preparing for his breakthrough book about the Dachau Jews who were thrown out of town that darkest of nights in November 1938 – Vor Sonnenaufgang (Leave Before Sunrise). After that she found it easier to speak about what had happened: she would tell us the facts when we asked about them. But the emotions of what she suffered were locked away, like the letters from her parents, locked away in the trunk on the landing of our house. I confessed to the audience that I’d once opened that trunk in her lifetime, when she was out of the house, and found the transcription of the letter Vera wrote on the train as she was being deported to whatever destination in Nazi-occupied Poland (most likely Auschwitz, or possibly Warsaw).

Press coverage

The stories waft around the stage for almost an hour and a half. There is no clear structure, the microphones have dropouts, and mostly English is spoken, sometimes German, but none of that matters. On the contrary, it suits this attempt to find words where darkness and the patina of many decades often obscure the memories. But not everything reported on this stage is dark. In his intensive examination of his parents’ history and the material they left behind, he realized that “the Holocaust affected people who were pretty normal,” says Stephen Locke. His grandfather Hans Neumeyer was a man who liked to go hiking and laughed a lot. A blind music teacher who was still composing even in the Theresienstadt ghetto…

…The evening could go on forever. The stories are probably never finished. And yet, shortly before the end, the entourage on stage turns back to the present. Müller-Hohagen asks how the guests see the world now. Stephen Locke answers without beating around the bush and in German that his view of Germany today is a positive one. Despite everything, he has become one of its defenders. There is a burst of applause, almost as if the audience is relieved at a little absolution. But the present is not one that promises relief. Nicolas Locke agrees. “The consequences of the Holocaust never end,” he says. “In the Middle East, two powers are trying to destroy each other. Without any sense.” The only way out of this eternal repetition is the unconditional recognition of others for what they are: human beings. And although the perfect final sentence seems to have already been spoken, his brother Tim digs up a quote from his grandfather Hans out of his long-term memory. Hans’ story taught him one principle, he says: “Not to hate”. Not to hate.

Sud Deutsche Zeitung: Landkreis Dachau. Click here to read the full article in English.

“The lively dialogue, delivered in English, shows that many of those affected have never spoken to their families about what happened. It is all the more important that the descendants agree to do remembrance work for their families so that this part of the past is not lost.”

Münchener Merkur: (click here to view the full article).

Finales

We dine late into the night at the Italian restaurant across the road, with acquaintances old and new from the town: I sit next to Björn Mensing, the pastor of the Chapel of Reconciliation at the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial – he has had that job since 2005, and very early in that job he met Nic and our mother Ruth. We’ve remade acquaintances with Tobias Schneider and Tanja Jörgensen-Leuthner from the Kulturamt who sorted out all the details of the trip, as they did when we last visited in 2018. At this finale dinner there’s a wonderful atmosphere of bonhomie, and in the impromptu speeches the Mayor Florian Hartmann says it’s like a family reunion.

An events organiser from the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial said the panel discussion was the best event at the Dachau November commemorations for many years.

And Jürgen emails us afterwards with the following anecdote about what happened a day or so after we’d left:

I would like to describe something very special: In our bakery, a young shop assistant whom I had never seen before suddenly spoke to me: “Aren’t you the one who spoke at Ludwig-Thoma Haus the other day? I only recognised your voice because I was sitting in the back row with my friend. What was said there was so good. It gave us goose bumps.” Wow! I asked her if she wanted to tell me her age. “Eighteen.” Wow again! So young and such a reaction! That gives us hope. That’s what I said to her.