When in 2012 we were clearing the house my mother Ruth had lived in since 1956 – and where I was born – I spotted an untitled audio cassette tape lying in on a stool in the breakfast room. I played it, and to my immense surprise found that it was an hour-long interview with an archivist from the Imperial War Museum (IWM) about her experiences during the Hitler years in Dachau and her wartime in England. She had never told me about this.

I’ve listened through it several times over the past few years and edited extracts for this blog. Recently I renewed my acquaintance with it and realised the small details I’d missed or forgotten. So here is the full transcript, with my notes – they bring so much to light, but curiously what she doesn’t say also hints at more.

Her style of answering is vintage Ruth. She launches into anecdotes and has a brilliantly clear memory for certain events; but then she mentions people’s names without really describing who they are, and mentions other people without giving their names. She sticks to the story she wants to tell and skirts round the more uncomfortable bits. I love to hear her voice again, but there’s something about the way she holds information back that frustrates me too.

You can hear the entire interview on the IWM’s website at https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80025041. The interview is in two parts, each lasting just under 30 minutes – scroll down to the bottom of the page and you’ll see two boxes: the one you are listening two has red lines around three sides.

The interviewer is Lyn Smith, who has done many oral history recordings for the IWM.

[My comments are in square brackets and in italics.]

The interview: tape 1

Tell me something about your family background – where were you born and when?

I was born in Dachau on 17 September 1923.

What sort of family were you born into?

That’s very complicated. My mother came from Silesia and she was born in Görlitz. My father was from Munich where his parents had a factory for clothes in Munich and my father became blind when he was 14 and then studied music. He went to Hellerau which is a school for Dalcroze with eurythmics and music and he was a teacher there in harmony training and ear training. My mother went to the same school later on and that’s where she met him.

Did you have any brothers and sisters?

I had one brother

Was he older than you?

No he was younger?

What was his name?

He was called Raymond.

That’s a very English name

Well in German it is Raimund.

So what was your childhood like?

We had a very good childhood. My mother was very keen for us to join her classes in eurythmics. She gave many classes, quite a few in our house for adults and for children. She went to various schools and convent schools to teach the nuns how to teach eurythmics to young children, and she organised plays in our house once a year around Christmas time and a lot of children from school or her classes took part in it.

[Ruth at this point jumps ahead to the most significant event of her childhood when living in Dachau, a story she told us many times:]

We did a very lovely nativity play round about 1936 which attracted a lot of attention but on another occasion probably about a year later we had a different sort of play and everything was ready, and we had about 40 people watching and about 15 children in the play when we heard the doorbell, and up came two SS people who shouted at everybody how they dared to go into the house of a Jew and took all their names down and addresses, and the children all cried and were all sent home.

And a sort of uncle who was helping us was taken and sent to prison because he was helping all the children and girls and calmed them down. And they thought that wasn’t the sort of thing to do for a man.

And that was really the end of our plays. That was I think in 1937.

[Actually more likely to be 1938, according to information I have subsequently uncovered. The ‘uncle’ was Julius Kohn (‘Onki’), the lodger; he was sent to Dachau concentration camp for two weeks after this event, and never spoke about it. In 1943 he was deported to Auschwitz. More about him here.]

Could I ask you about the religion of your parents?

My father was Jewish but not orthodox or anything, and didn’t go to anything. My mother was Protestant.

Were you brought up in either of those faiths?

Yes, as a Protestant. In that again I was an outsider because most of the people in our class were Catholics and there were only four Protestants so we were always sent out when there was religious instruction.

So that made you an outsider?

I was always an outsider. We had no links with Judaism at all. Very first time I went to synagogue was about two weeks ago when we had this Holocaust Memorial Day in Lewisham.

Was there anything in the home that related to Jewish culture?

Not as far as I know. We didn’t know that we had some sort of Jewish background until I was about 12 when all the BDM [Bund Deutscher Mädel – the equivalent of Hitler Youth, for girls] and Hitler Youth started and they said why don’t you come but of course we couldn’t.

[This seems surprising considering that Ruth’s father and his family were Jewish and her mother’s father, Martin Ephraim, had been a prominent Jewish industrialist. More on the family’s Jewish businesses here.]

Was that a shock when you realised the situation and how you related to it?

We suddenly realised we were different.

[I think Ruth is keeping a lot back here; Lyn, the interviewer is delving gently and expertly.]

That was when you were twelve years old?

Yes, about that.

So what did it mean to you when you were accused of being Jewish? I wonder what you felt about that or what you knew about Jewish people?

We didn’t know anything except they were jolly rotten people and called saujüde. We knew very little about it [Judaism]. I think it was the sort of time when parents really kept children innocent and they didn’t really share their troubles, not like Anne Frank who always shared her troubles with adults. We were rather sheltered and our mother always tried to do beautiful things with us like plays and dances and outings to the mountains, and long walks and that kind of thing.

[Does Ruth get her words in a tangle here or is she describing what she was told about the Jews at school?]

Hitler came to power of course in 1933. Apart from the play in around 1937, when did it start to impinge on you? Can you remember the early events?

I think it was, I can’t remember the date, but it was in this Protestant school and they were trying to do this Christmas play and they thought it would be safer not to include us, and they apologised. We didn’t quite understand it but we thought it was a silly play, anyway. And that was it.

It is extraordinary how children really are very resilient. We still had one or two friends from school who didn’t seem to mind. We had some very loyal friends there in Dachau, actually. There was an artist woman who was a great friend of my mother, very supportive. We had very simple people, lots of peasant people who came and helped and occasionally we went to their house and they gave us a wonderful meal or they gave us some extra fruit – that sort of thing.

[The artist woman was Aranka Wirsching (1887-1956), whose son Anselm was taken as a prisoner of war by the British and wrote to Ruth from a POW camp in Egypt during 1946-47. The ‘peasant people’ may have been the Steurers, who feature elsewhere in this blog.]

Did it affect your living standards?

I think it must have done because we had very little money. My father wasn’t allowed to earn through his music and my mother gave language lessons and eurythmic lessons in different places. I think she was the main earner.

You would have been known as Mischling, being half Jewish.

Probably.

[Not true! Ruth and Raymond had three Jewish grandparents so by Nazi law they were fully Jewish.]

Did that come into it at all?

No I don’t think so.

Yet you seemed to have the full extent of discrimination – is that right?

Yes, probably. I was actually confirmed in Dachau. We had a little Protestant chapel.

[For more on her confirmation, see here.]

So you felt Christian, did you?

Yes, I felt very Christian.

[Christianity was hugely important to Ruth during the war years in particular. I don’t think she ever lost her faith but the intensity seemed to fade later on, perhaps when she discovered her parents had died in Nazi camps.]

How about your education? How was that affected?

Education was pretty awful because the usual way was that children of families who were more educated in Dachau – most of them were actually quite simple children of cobblers, farmers and so on – were sent to Munich, to a grammar school. But my family couldn’t afford that. We didn’t know that but we couldn’t afford it, so we stayed all the time in ordinary secondary schools.

I was wondering if anything happened before then [Kristallnacht] that was significant to you. Were you aware of the growing strength of Hitler and the impact of Nazism? What was Dachau itself like as a town at that time? And how compliant it was and whether there would have been banners about?

There would have been banners about, and when Hitler came to power there was quite a nice Burgomaster, and he said ‘Just roll up your Bavarian flags, keep them in the loft, and you’ll be able to use them again soon’. After that there were of course flags all over the place and processions. It’s difficult to remember all these things.

Dachau was made into a town some time in ‘37 or ‘36 which meant it had 8000 inhabitants – and there was a great big festival with flags. We took part in that, a bit gingerly, but we did and it seemed to be all right. But after that people did make a nuisance of themselves and quite often they threw stones at us and shouted ‘saujüde’ and so on.

[Dachau actually became a town in 1933, when the Nazis came to power. She may be confusing this with the ceremony in 1935 for the opening of the new section of the town hall .]

Did you know anything about the camp?

The camp was very hush hush. It was quite a way out of Dachau. The old town is situated on a hill and farming land around it. And round that is flat moorland which created beautiful light and a lot of artists settled there and painted – Dachau is quite well known for artists and they still send me very nice calendars of different artists every year.

[Ruth really didn’t want to talk much about the camp, and always maintained that Dachau was primarily an artists’ community. So at home we had lovely books on Dachau artists, and a Dachau Sparkasse art calendar hanging up in the loo, where there was also a decorative tile of Dachau. And by her bed was a picture frame with photos of her mother and Dachau’s old town – the castle and Jakobskirche.]

But when you went for walks and got anywhere near this camp, no one said anything – they said it was a powder factory and some people get sent there – no one spoke about it but you knew there was something sinister behind those walls. But it didn’t really start to be really awful till much later, when dreadful things happened.

Um, what else? Yes, I think it was in ‘37 when we weren’t allowed to go to school any more. It didn’t affect us. We were quite glad. We thought it safer not to go to school. But we never understood why my parents didn’t decide to leave Germany. They could have done – they had contacts in Switzerland and in Sweden, in Italy – well Italy wouldn’t have been any good either.

It wasn’t until my father remembered a pupil he had from England in the Dalcroze school in Hellerau that they started to write to ask whether they could find guarantors for us to come over, because that was after we had been thrown out of our house, after the Kristallnacht, and we were in semi-hiding in Munich for some time. The correspondence then started with this family in London who were very, very kind and found funding for us two – my brother and myself – to come to England. My parents were hoping to come and follow us, after they had settled their affairs – they had to do something about the house in Dachau and some personal things I don’t know [about], but of course they didn’t manage it.

What was your experience of Kristallnacht? Could you take me through that? This would have been in Dachau?

In Dachau, yes. We just come back from a holiday in Italy. My father was in Berlin learning how to make flutes and my mother and the two of us were alone in the house, when about 8 o’clock two people from Dachau town hall including the burgomaster arrived to say we would have to leave the house at sunrise the next morning or else be sent to prison.

My poor mother didn’t know what to do and asked the Protestant vicar and asked him for some help. He said he couldn’t do anything for us should just go so we packed a case and left before sunrise and went to Munich, to the station there. We had a yoghurt in the Molkerei and for some reason people guessed we were a bit odd arriving with case early in the morning and said they didn’t want us in the station.

[Hans, Ruth’s father, was a practical man but a flautist friend has told me it would have been extremely challenging for him as a blind man to make flutes. I think Ruth probably meant recorders. But this isn’t the full story by any means: Hans was in Berlin with his secretary Dela Blakmar, with whom he was having a passionate love affair; in July 1938 the two of them were applying to escape to New York. More on that story when I manage to locate the letter (now in an archive in New York) that he wrote to Herbert Fromm, a Jewish composer friend.]

Luckily my mother had quite a lot of pupils in Munich and managed to get us into the loft of one of her pupils where we stayed for some days until some alternatives were found and my brother and I were sent to different people. I went to a family in Munich who were also Jewish and had two girls; I don’t really know where my brother went. But eventually after some weeks a Jewish doctor let us have two rooms in his flat and we stayed there until we came to England.

And my father came back from Berlin, and they allowed us to go to Dachau to settle his affairs with the banks and so on. The house was sealed up, and I think they were allowed to organise where the all things were going to go, and that was it.

[Ruth didn’t remember all the places they stayed at, and to what extent they were in hiding is not clear. From later in this interview it transpires that the first family they stayed with was the Lesers; Frau Leser and her daughters later escaped to England, and Ruth kept up with them for many years afterwards. The ‘doctor’ was Dr Köbner – Ruth’s mother Vera reports in her letters that she finds them difficult to get on with, though her husband Hans and his friend and colleague Dela like them.]

Did you see any signs on Kristallnacht, because after all you would have been travelling through the night, of what had happened, of any destruction?

No, we didn’t but it was only 12 miles from Munich and it was all countryside really.

[We understand that the expulsion of Ruth’s family happened a day earlier than Kristallnacht, which would mean that the Neumeyers – Vera, Ruth and Raimund – were in a friend’s attic in Munich when Kristallnacht happened. Presumably they saw and heard nothing there.]

Had anything happened around you? Were there other Jewish families living in Dachau?

There were only two other families in Dachau. There was one family lived near us – they had the same fate – it’s in this book. [Hans Holzhaider’s book about the Jewish families of Dachau – Vor Sonnen Aufgang. She is talking about the Wallach family, who owned a textile factory nearby. Their son Franz Wallach escaped to England where he changed his name to Frank Wallace].

There were very few of them?

Oh very few. Just one family and one or two individuals. There were no more than about 10 or 11 people from Dachau that they had the pleasure to send away, but there were five people who were affected by this who later on died in concentration camps, and these were the people I wanted to have commemorated by the town of Dachau rather than by the camp, because it had nothing to do with the camp.

Eventually the burgomaster of Dachau agreed to put a plaque up with the names for this five citizens of Dachau for the opening of this exhibition. And from then on they have a memorial service every November 9 – they put a wreath down and they have schoolchildren sometimes taking part in it – which I think is very good, and I’ve been sending messages to them quite often on this occasion.

[The exhibition was in 1988 in Dachau town hall: the plaque was Ruth’s initiative, though it needed some coercion from Hans Holzhaider.]

It’s very interesting in that your mother was not Jewish.

Half Jewish.

[Her father was Jewish, her mother was not.]

Oh I see. Although she was Protestant by religion, and your father was Jewish. Did they give you any category for that degree of Jewishness so far as you knew? Would have you been more than a Mischling?

We would have been three-quarters, my brother and I.

[This is not correct. Ruth and Raimund had three Jewish grandparents, which by the Nuremberg Law of 1935 made them totally Jewish in the eyes of the Nazis.]

What were you thinking all this time that all this was happening to you, because you were identified as being Jewish? Because you were a young woman, fourteen or fifteen?

I knew we were three-quarters Jewish, but it wasn’t called Jewish – it was called ‘non-Aryan’, which is a little bit different – ‘nicht arisch’ they used to call it.

And did you understand that term?

Yes. Only occasionally this ‘saujüde’ came out – and that of course was silly people who couldn’t distinguish between religions and so on.

Were you concerned that you are an Aryan-looking person – did you feel any different from the others?

No, I didn’t feel different. In Bavaria you get lots of dark-haired children and brown-eyed children, probably more than the fair ones, because there are all the Prussians up there. Anything north of the Danube was foreign to us. We were very silly, I think!

[Ruth always retained a sort of ironic snootiness to ‘hoch Deutsch’ and anything ‘up north’.]

How was it that your father managed to get you on to the Kindertransport?

How that was actually arranged I don’t know. All I know is that we got our different papers which took ages to get with lots of queueing up at offices and then your passport. Then you had to take to take a photograph of your left ear, of one of your ears showing. We had to have everything we want to take out of the country displayed. One evening an official came to make sure we were not taking too much out of the country.

We were allowed to take two forks, two knives and two spoons of silver with us. [These was monogrammed silver cutlery bearing ‘MHE’ — the initials of Martin and Hildegard Ephraim, Ruth’s maternal grandparents. We used this cutlery in London for decades. There was also a silver christening spoon engraved ‘Ruth’ , which we rather rashly gave away to someone.]

My mother had bought me a new dressing gown made of towelling. It was red with white dots on it and she thought ‘just to make sure that they don’t think it is new I shall soak it in water’ and there was this thing in the bath of water when the man came to see if it was okay. And I’ve still got this dressing gown. We sometimes used it for Father Christmas because it was red!

We were allowed to take a trunk and a case each and were just told you’re going on this train which will go to Holland and from Holland to England. Your new people be collecting you at Liverpool Street. The night we were leaving we were feeling very mixed and sad, and the middle of the night was even worse. Our parents came with us to the station.

In some ways we were fortunate because we were travelling with two friends my mother managed to introduce us two, two young children who were coming on the same transport. So we were together all the time in the compartment and we didn’t really notice much else, which was lucky.

[These children were Walter and Clarisse Nathan, who went to live with the Bovey family in Paisley: click here for their story, which includes reminiscences from Clarisse about the Kindertransport journey.]

During the night we must have slept a little bit and we were woken up once by some SS officials wanted to look at our papers and we thought probably something awful thing was going to happen but nothing happened luckily. In in the morning we arrived in Holland and were greeted with cocoa and white bread which was most unusual. I can’t remember the ship at all, but we must have got on a boat to Harwich and arrived in the afternoon. Then we went down by train to Liverpool Street and waited in the hall there to be collected, which was very lucky.

The people of course who took care of us were wonderful. I remember going in a taxi from Liverpool Street to I think it must have been Waterloo, because we went to Weybridge after that – and on the way we were shown the Bank of England and St Paul’s on the way, and Trafalgar Square. My brother went to a different family but the people where we stayed with in Weybridge were relations of the pupil of my father’. We were there – my brother went to a different school and I went to the Hall School, which was a wonderful private school in Weybridge. It was the first time I ever enjoyed being in a school.

[Frank and Beatrice Paish met them at the station; they were the guarantors – Beatrice was the connection, having studied eurythmics with Vera and Hans many years before. Ruth and Raimund went to stay with Oscar (Beatrice’s brother) and Doris Eckhard in Weybridge.]

How about your language? Did you speak English at all?

No, I think my mother tried to teach us a few words of English, so we could say a few sentences, and we tried to practise them. We looked in a very old dictionary or phrasebook – there were some phrases of endearment, and we thought we’d better learn some. There was a very stupid one which said ‘Hullo, how are you, old horse?’ – that was supposed to be a term of endearment – it must have been from the 18th century or something!

[Ruth used to say that she didn’t remember making a conscious effort to learn English – it just happened. Her mother’s English, though, was very good and I would have thought she must have taught her children a little in the weeks before they came over. She didn’t really have a German accent, though there is a hint of something discernibly different that comes over on this recording. Raymond, on the other hand, never lost his German accent.]

They were very, very nice and when we arrived there was an enormous round table with all the family – two girls and all the parents, and masses of food – we’d never seen so much food: there were scones, and cake and jellies and salad and sausages. We had forgotten that in England when you are asked if you want any more you say ‘no thank you’ – we kept on saying ‘thank you’ and they gave us more and more! But we soon learned.

[Ruth loved the ceremony of a communal meal together – not the ostentation of the cooking but the fact that there was plenty and everyone was there. In my childhood I remember her telling us to lay an extra place at table ‘for the unknown soldier’ – in case anyone else unexpectedly turned up.]

The interview: tape 2

I suppose culturally there was a lot to learn, wasn’t there?

There was an enormous lot to learn. My education had been really terrible up to then. I found that the school I went to was a revelation. It was free, it was quite small, we did the most wonderful things, history was fun, mathematics was quite good, English you had to learn a poem straight away and recite it in the hall and had to take part in a play, Macbeth.

The art was absolutely fantastic: instead of doing little drawings with a little flower standing in it you had a big sheet of paper and powder paint, and for homework you had to produce a big painting. On Monday morning they were all pinned up on the wall and we criticised each other’s pictures. One suddenly learned to live and it was absolutely wonderful.

[Ruth attended art college in Canterbury in 1950, studying under Eric Hurren. While on the course she created a wooden sculpture of hands which she said was the memory of her father’s hands.]

And they also had a marvellous Dalcroze teacher. They performed a Bach fugue with three girls and it was absolutely lovely. Unfortunately the war broke out, the school evacuated to the country, my family had to stay behind because they had a little shop there and had to look after that.

[Dalcroze was a method of eurythmics – a discipline connecting music, movement mind and body, and designed to foster ear-training, improvisation and music improvisation — which Ruth’s mother Vera had taught. Dalcroze courses are still held in Britain.]

But the other part of the family who initiated all this asked us to come with them to Wales. We spent the whole summer there and were there when the war broke out. We were told ‘it won’t last long and your parents will be all right’. We had to stay in Wales a bit longer because the husband , Professor Frank Paish, was at the LSE, which evacuated to Cambridge.

It was Mrs Beatrice Paish who was a pupil of my father’s. So they said ‘would you like to evacuate with the school to the country or come with us to Cambridge, because we have some more relations there and you can stay with those relations?’ So I said I would like to go to Cambridge and had got to know those people because while we were in Wales and we had performed a little play, Hänsel and Gretel and all the children there – there were lots of people, all the family, camping and so on – and I had the most marvellous time in Cambridge with this other family. We wrote our own plays and produced things, and made a thousand and one things all over the house. I started to learn a little more – botany, English and history – but then everything was changed.

Ruth’s illustration for a children’s project on Hansel and Gretel when doing teaching practice in 1949. The fairytale evidently struck a deep chord with her. Her mother had produced the play-with-music in the Neumeyer house in the 1930s and when I was a child she got my brothers and neighbours’ children to perform it in our house in London in the early 1960s, with one or two songs from Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel, her favourite opera. The story of two children lost in a threatening forest, defeating the evil witch and finding their long-lost parents has somewhat uncannily close parallels with Ruth and Raymond’s experience.

In Cambridge, did you meet other refugee children?

Not at that time.

I understand there was quote an organisation in Cambridge – Mrs Burkill – do you know her?

Yes, but not at that time. The family I was stayed with was attached to the Lees School – he [John Stirland] was a senior master there. The Lees School evacuated to Scotland and it was more important for me to stay on in Cambridge and learn a bit more, then Mrs Burkill and the Refugee Committee started coming in with all these things, and they had a hostel for all these refugee girls to learn domestics so they could at least do something useful and didn’t get sent to the Isle of Man.

[Many refugees were sent to a camp on the Isle of Man during the war, but fortunately Ruth avoided this bleak hardship.]

So I was in this hostel for six months and we learned how to iron handkerchiefs, how to wash up and how to cook things and so on and so forth. Then the Refugee Committee asked me if I would like to learn something else and what I would like to do. I gave them the alternatives: I would love to paint stage scenery or else I could work with children. It was decided it was safer and better to work with children, so I was sent to Wellgarth Training College – it used to be in Hampstead, but it had been evacuated to a country house near Swindon.

[The hostel was St Chad’s in Grange Road, Cambridge.]

Your time in Cambridge and the Refugee Committee – was that a good, tight organisation?

I think it was, but I didn’t have very much to do with it.

What about Mrs Burkill – what did you think of her?

I didn’t come across her very often, but she was very nice, very excitable, a little bit bossy. I think she did a lot for us all – there was this club, the 55 Club I believe, that was for refugees, but I didn’t go there very often.

But after this training at Wellgarth, where they were supposed to find wonderful jobs for us and I insisted I didn’t want any of their jobs as I was going to find my own in Cambridge again. I came back to Cambridge, and after that I saw the 55 Club people a bit more often. There was of course a wonderful clergyman called Pastor Franz Hildebrandt who used to hold Anglo-German services at Christ’s College Chapel every so often. All the girls I knew were very keen on going there – he was a rather smashing sort of a person, very good to talk to – he had something to do with Pastor Niemoller.

[Pastor Hildebrandt was a Lutheran of Jewish descent. He was a friend of Pastor Martin Niemöller – both men set up an organisations in Nazi Germany to help pastors affected by the Aryan Paragraph. Both men were arrested by the Nazis and Niemoller was interned during the war in Sachsenhausen and Dachau concentration camps. Hildebrandt was released and came to Cambridge where he was instrumental in building up the Protestant congregation. He presided over the wedding of my parents Ruth and Ronald in 1951.]

So he attracted young ladies to his services?

No, there were not many people who were Protestant and Jewish and living in Cambridge.

Had you had contact with your parents at this time? Leaving on the Kindertransport, what was it like leaving your parents on the station? Did you have any idea that you might not see them again?

I had no idea – we were quite certain we would see them again.

Were you in touch with them subsequently?

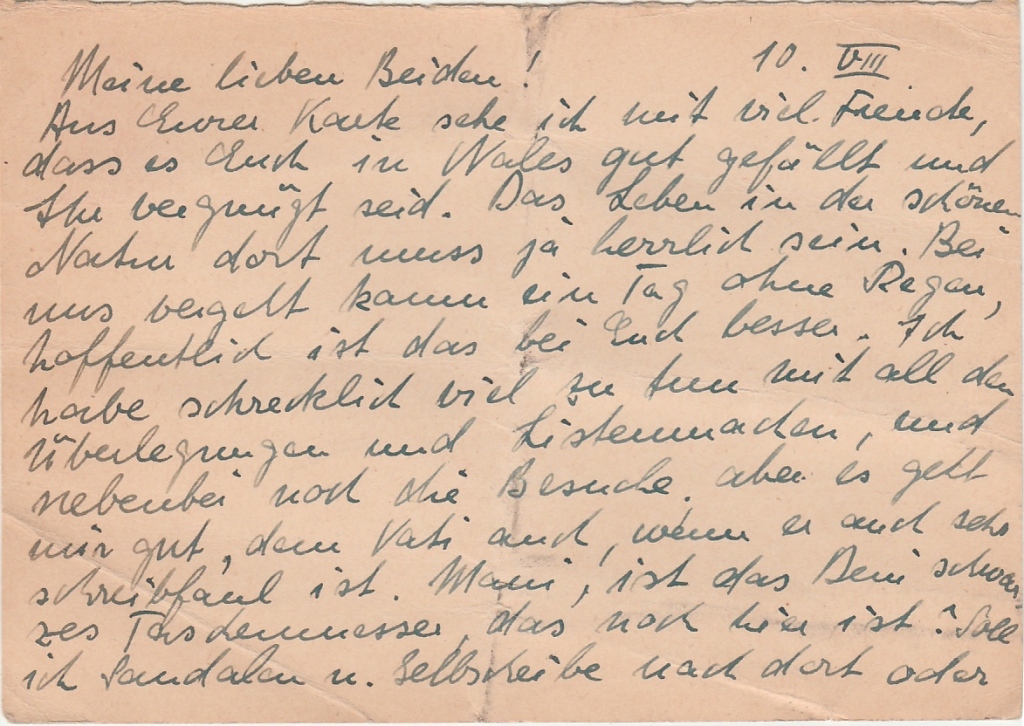

We wrote letters until the war broke out and they wrote letters to us, and told us what was happening, but they always covered up any awful things. Later on there were the Red Cross messages that one was allowed to send once a month with 20 words [actually 25 words], and they went via Switzerland and the answer then came back a few months later. They went on – I’ve still got them here actually – until 1942 when they were deported. They just said they were ‘going away’, and that was that.

And did you have any idea where they might be?

No. We thought my mother might have to go to a work camp – that’s what it was called. I didn’t know until after the war that my father was in Theresienstadt and my mother was somewhere in Poland – one of those concentration camps there.

[There’s plenty elsewhere in this blog about her parents’ fates: Hans in Theresienstadt, and Vera in eastern Poland.]

Was your father ever sent to the Dachau camp?

No, we had nothing to do with Dachau at all.

[Ruth revisited Dachau several times after the war, to see friends and attend commemorative events in the town, but apart from an event in the chapel there she never visited the concentration camp memorial.]

I understand he composed a piece of music?

He composed lots of music, but all of it got destroyed and there were only two little works which a friend of his, a colleague of his, who was Swedish, had – she was a viola player – she sent them to us a long time after the war. One is a duet for violin and viola, and the other is a trio for violin, viola and cello. They still exist and I hope we will do something about it one day. I have got a recording of it which some pupils did at Trinity School of Music with Bernard Keeffe – he tried to do it on a tape – it gets interrupted by a police siren and they start again – I thought it was rather typical!

[Ruth would have been pleased to know that the surviving music of Hans Neumeyer has in the past few years been played at numerous concerts and events in several countries.]

Did he compose them specially for you?

No. He composed them for his pupils. He had a flat in Munich, and a grand piano there (as in Dachau), and taught in Munich privately.

I have heard he composed a tune specially for you after he had left?

Yes, I’ve got that here. It came via Switzerland and I got it in Cambridge when I learned to play the recorder with one of the girls [Jane Stirland] in the household there, and we used to play duets a lot – anything we could find – and he must have heard about these in the Red Cross messages – and he composed these two little pieces, sent them to a friend in Switzerland, who was a musicologist, who managed to send them to us. We got them during the war somehow.

[The musicologist was Gustav Güldenstein (1888-1972) from the Basel Music Academy. He taught rhythm, solfège, harmony and improvisation there from 1921 until his retirement in 1953. He was a colleague of Hans, and a family friend who kept in contact after the war and wrote a letter to Ruth about what he thought had happened to Hans. We think it likely that all the letters sent after the outbreak of war between the Neumeyer parents and Ruth and Raimund went via him in Riehen, Switzerland. ]

That must have been very precious to have had something specially composed for you, for your recorder?

Yes. The timing of this music is very difficult, but I’m hoping someone will do it properly with two recorders, then it will be nice – then you can have it.

[I first heard it performed by children on 22 June 2016 at North Herts Music School. To see the story, click here.]

So their letters were cheerful to you, were they?

Yes, they were always hiding the awful things – I think people always did that. It wasn’t the generation when adults talked to children much and worried them with their problems.

[And Ruth certainly kept the worst of it from me and my two brothers during our childhood and afterwards. She never really let on to us how it had affected her.]

Were you having any problems at all – from what you’ve been describing, everything seems to have been going very well. But were you feeling homesick?

I wasn’t feeling homesick at all because I must have felt the oppression in Germany and I also found that there was tension between my parents at that time. And I felt so relieved to leave everything behind. That seems quite awful.

It must have been a very strainful, stressful time for parents, with things deteriorating so much, and particularly as you say hiding from you?

Yes, it’s very strange because my mother had two sisters who had survived the war in Germany. One had married an Italian and she would have been half Jewish, and the other one just survived. They were both in the northern part of Germany, and I think they felt very guilty. My mother before she was deported had sent a telegram to one of her sisters saying ‘please come to Munich, I may have to leave’ but her sister wired back to say ‘I haven’t got a travel permit, I can’t come’. But one of the first things one of these aunts said to me when they came here once was ‘I couldn’t help it, I couldn’t get a travel permit, I couldn’t help your mother’. It must have been very awful for her. She always said ‘I think she’s still alive somewhere’ but we never found her.

[She is referring here to Janni, her aunt, whose letter confirms this story.]

When war started in September 1939 was that a big blow for you?

Yes, it was a big blow, but Mrs Paish was very nice – she came and sat on my bed, and said ‘It won’t be long, your parents will be all right and we’ll look after you.’ We were comforted and we were at a time when lots of new impressions come into your life. Everything was very positive.

Were British people kind to you?

Yes, very kind. People were very kind – I really did feel at home, especially the two girls I lived with in Cambridge, we did so much together. One of them once wrote to me and said ‘we didn’t know how nice life could be until you came’. That was really nice! And I’m still very much in touch with all this family and go to their family ‘cousin’ reunions.’

How about your work situation? You were saying when you left your training you were determined to find your own job. How easy was that? You were trained to look after young children, were you?

Yes, it was very easy. There were war nurseries – I got a job in a very nice war nursery and I stayed there for quite a long time until I did my teacher training.

Were these nurseries specially set up for women working in the war effort?

Yes. They were from 8 o clock to either 6 or 8 o’clock at night and the children were there all day, the children slept there and had their meals.

Was that a government-run scheme?

Yes. First we weren’t allowed to own a bicycle or leave the town without police permission for more than 5 miles radius.

Is that because you were a so-called enemy alien?

Yes. I soon discovered when I came back to Cambridge in 1943 that if you offered to do fire-watching you were allowed to be out at night and have a bicycle, which I did, fire watching from the roof of a church [Great St Mary’s] in the middle of Cambridge, which was very exciting.

Were there some raids?

There were some raids but nothing very much. We had a sort of cellar with bunks in it in the first house. Some windows were blown in in some of the colleges.

How about your brother? Did you have contact with him?

Yes, I had contact but his life was very different. I don’t know if I should say this really but his guardian didn’t really care very much about him, which was a pity. He did very well at school but was told to leave as he was going to be sixteen soon and it would be better to work on the land. He absolutely hated farming and ran away twice. He eventually landed up in Birmingham at a bicycle factory, where he did his Matric, then he joined the army. He had to change his name.

By the time he was actually posted somewhere it was the end of the war and he was in Germany in the occupation force and had a lot to do with the intelligence corps.

[For more on Raymond’s story, see here.]

Did you want to go into the forces?

No. I think I did my war work in the war nurseries.

Did you get to meet the mothers of the children?

Yes, I got to meet the mothers. They were working in factories mostly, or [doing] anything that was short of manpower. It was very nice for them to have the children completely looked after. They [the children] were fed, and washed, and all had little beds, had their rest, had stories read to them, were taken for walks. This must have been all free. I think our pay was £2.10s per week – I paid 10s for my accommodation. I had a room in Professor Ginsberg’s house in Cambridge, which was absolutely lovely, they were very nice people and I had quite a lot of freedom there. He was also at the LSE of course. I suppose Cambridge was really the background to my younger life.

[For more on Ruth’s Cambridge years, click here.]

Did you have a good social life?

We knew quite a lot of people

Were there a many young refugees?

Yes, there were a few, especially some twins who I am in contact with – they’re still in Cambridge. There was a group of singing people and we got together and sang opera in the Refugee Club. We did a little bit of the Freischutz and a little bit of Carmen, which was quite nice. I tried to learn the piano but I wasn’t very clever.

What is your memory of VE Day?

I had got to know someone [Leon Long] who had got engaged to a German girl. She had to go back to Germany. At the end of the war the whole of Cambridge was celebrating and we were just very glad that the borders might be open again and we might find my parents again. My brother was in Germany and managed to contact his [Leon’s] fiancée. So they got together. After that I went into teacher training.

[Leon Long and his brother Denys were both very close to Ruth. From letters it seems they both had romantic attachments to her. However, while stationed with the British army in Germany in 1946 Raymond sought out Leon’s fiancée Maria, who had got engaged to him before the war, and brought the couple back together. They married soon after, and Ruth was a bridesmaid at the wedding. It was a curious set-up, and I never worked out what Ruth made of it, or if she was by then closer to Denys or to someone else. For more about her time at VE Day, click here.]

When did you find out about your parents?

It was in 1945 in September. It came via my brother and the Red Cross – he made some enquiries where they had died.

Did you know anything then about the reality of the Holocaust?

No. Not really, it came much, much slower. My brother had to go to some kind of denazification court and also there was something in Dachau where people had to state that they knew us – and we were supposed to be ready to answer questions. We had a pupil of my mother’s who was actually in my class once, and she was so worn out by this that she fainted in this court case. But there was something about our house of course – we were trying to get our house back again.

[The people in Dachau were the Wirschings. Ruth and Raymond were asked by Aranka Wirsching after the war to write to the authorities to confirm that her son Anselm, who had served in the German army, was not a Nazi.]

Did you manage to do that?

After a long, long time we managed to get the person (who actually bought it) under pressure to pay some more money – and she paid us some more money over about seven years of about £500, no about 500 marks. But we didn’t want to worry about it, we didn’t really want this house it was far too big, old. It was a very nice house.

Did you have any intention of returning to Germany after the war?

No, not at all. We felt in some ways very antagonistic towards Germany.

Do you still feel that?

I have mixed feelings. The only thing I really like about Germany is the mountains – and that’s right down in the Alps – and you get mountains in the Dolomites, in Switzerland and in Austria too.

[Ruth retained an ambivalence towards Germany until the end of her life. There were German books, pictures, letters and more all over the house in London, and German music and art were very important to her, but there was always something simmering just beneath the surface.]

Do you have any contact with the Kindertransport reunions or the people?

No, I don’t know anything about them.

It seems from your experience that you were very much on your own, very individual.

Yes.

Are you interested in being in contact with them?

Well, I met one or two people here at the Imperial War Museum – I met Bea Green and briefly met Anita Wallfisch, but otherwise I haven’t really – no one else from the Kindertransport. I know one friend very well – who lives in Nottingham – she was also in Munich. She was actually in Munich where I stayed for three weeks in hiding, and she came to Cambridge as well, before me.

[The friend in Nottingham was Ursula Leser, married name Leonard. They kept in close contact for the rest of their lives.]

Well thank you very much indeed, Ruth, for coming along today and telling me about your experiences, and I do hope that something happens with your father’s tune.

Yes, that would be nice. I don’t suppose this is very useful to you as I can’t really say very much.

[A classic Ruth understatement. She actually had an amazing amount of information and memories, but for a long time thought no one else would be remotely interested in any of it.]

Oh no, it’s most interesting, thank you very much indeed.